Space rocks streak through the Alaska sky

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

Oct. 7, 2021

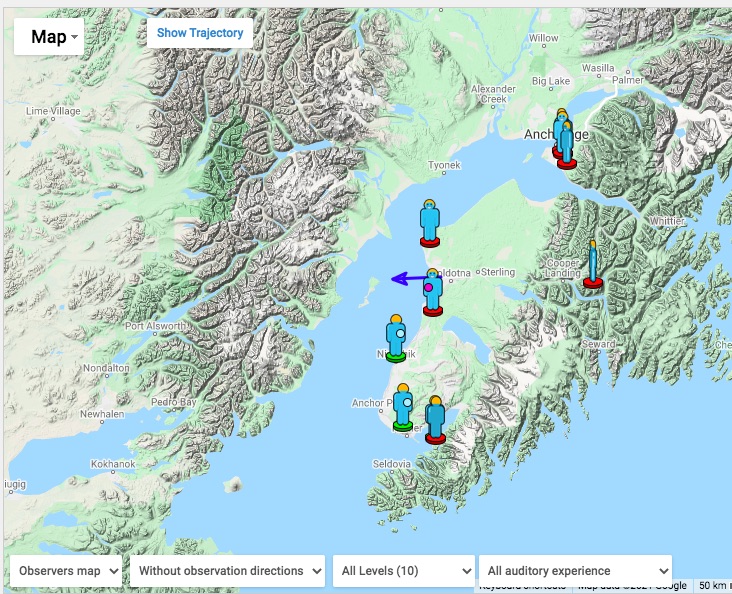

A screenshot of a website created for the American Meteor Society shows reports from Alaska residents about a fireball that exploded above Alaska on Sept. 30, 2021. The blue arrow is the estimated direction of the fireball.

About once every other week for as long as you have been alive, zooming space rocks have penetrated the shell of gases surrounding our blue planet.

If you happened to be in the right spot and were looking up, you might have seen a fireball in the sky, caused by a supersonic space rock encountering the sudden friction of gas molecules in our atmosphere.

Such was the case in late September, when people on the Kenai Peninsula and in Anchorage noticed a white streak slashing the black night sky. Some even heard a boom.

“I’ve seen shooting stars but this was giant in comparison. It was once-in-a-lifetime,” Holly S. of Anchorage posted on a fireball-and-meteor webpage on Sept. 30, 2021.

“Sounded like rolling thunder and lasted about 15 seconds,” wrote Jason S. of Kasilof.

“Two other people with me saw it,” said Kim S. of Halibut Cove. “It was the most incredible thing any of us have ever seen.”

They saw and heard a bolide — a large meteor that explodes in the atmosphere. Scientists farther away in Alaska noticed it too. Placed on the ground not far from where the meteor blew up are networks of sensitive microphones.

These infrasound networks are tools scientists use to hear sound waves, including some so low in frequency our ears can’t pick them up.

A cluster of six infrasound microphones installed near Kenai in 2020 by researchers from the Alaska Volcano Observatory and the U.S. Geological Survey captured the end of the space rock’s recent journey to our planet.

A screen shot from a NASA webpage documents confirmed fireballs that have entered Earth’s atmosphere from 1988 to the present.

Max Kaufman of the Geophysical Institute looked at spikes in the infrasound data and matched air-pressure changes to the behavior of the heavenly visitor.

“The bolide might only be visible for three-to-five seconds, but it left a trail of sound in the atmosphere that took 100 seconds to pass by,” said Kaufman, who often travels to the slopes of volcanoes to maintain seismic and infrasound stations.

Since people like Kaufman installed more than 100 infrasound stations all over Alaska, in Antarctica, and on humid islands in large expanses of ocean, scientists have detected nuclear explosions beneath North Korea from as far away as ĚÇĐÄvlogąŮÍř. Nuclear treaty compliance is the main reason for the networks’ existence, but scientists have over the years found them useful in ways they didn’t expect.

With the infrasound microphones, which are on all the time, scientists have also heard the roar of volcanoes, the dance of the aurora and — once in a while — the sonic pathway left behind by a fiery object that plunges toward Earth in a few blinks.

No one knows the fate of the blackened space pebbles that survived the recent journey from the infinite cosmos to Alaska, but scientists think it’s a decent bet a few are nestled in the ocean floor in Cook Inlet.

Since the late 1970s, the ĚÇĐÄvlogąŮÍř' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. This year is the institute’s 75th anniversary. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.